|

|

Rowlands Gill and Surrounding Area

|

Rowlands Gill

The town of Rowlands Gill lies on the

north side of the wooded valley of the

River Derwent, about four miles

upstream from Derwenthaugh, where the

Derwent flows into the Tyne. In this

book is gathered a collection of old

picture post¬cards, selected to

illustrate the history of Rowlands

Gill and district.

The oldest settlements in the area

were hamlets that existed in the days

of Saxon Northumbria. One such hamlet,

which was possibly raided by Vikings

and burned in William the Conqueror's

harrying of the north, stood at the

point where the road from Durham

crossed the Derwent, before going

north through Winlaton and Blaydon

Burn to reach the Tyne fords at

Stella. A record of the Prince Bishop

in 1361 named this hamlet

Huntlayshaugh. Even in those days

traffic through the hamlet was fairly

frequent, as anyone whishing to cross

the Tyne to avoid the authorities or

the bridge at Newcastle used this

road. The narrowness of the old

Newcastle bridge meant delays to any

drovers of sheep or cattle, which

ensured that the ford at Huntlayshaugh

was kept busy. In 1650 Cromwell used

it for his artillery train to avoid

the Newcastle bridge.

In 1691 Ambrose Crowley chose to

partly dam the river near

Huntlayshaugh. He used the water power

from the dam to drive nine millwheels

he erected there to provide energy for

an ironworks. The village which then

grew up around the works became known

as Win laton Mill.

During the 17th and 18th centuries

sword makers, who came originally from

Germany, settled further up the valley

at Blackhall Mill and Shotley Bridge,

to take advantage of the local iron

ore deposits. The industries of the

Derwent Valley were based on water

power and were generally quite distant

from their customers in the towns.

Toward the end of the 18th century the

advent of steam power allowed

factories to be built in towns much

nearer their markets. This spurred on

the local firms to think of ways to

im¬prove their competitiveness. The

best way was to improve delivery times

and cut down transport costs. Although

wooden railed wagonways had developed

in the district dur¬ing the latter

part of the 17th and 18th centuries,

these were only used to deliver coal

to staithes on the Tyne. The products

of the ironworks and other goods had

to come and go by road as far as the

Tyne.

Thanks to Crowley's dam, the fast

flowing Derwent was not navigable

upstream from Swalwell. At this time

most coun¬try roads were little more

than cart tracks, with frequent gates.

For example anyone wishing to send

goods to Blaydon from Blackhall Mill

had to face a journey that included

open¬ing and closing forty gates

between Blackhall Mill and Coal¬burns,

where the cart could join the Lead

Road to Blaydon. In addition, as the

upkeep of most roads was a charge on

the parish, the roads were quagmires

in winter and heavily rutted in dry

weather. It was therefore decided to

build a turnpike road from Axwell to

Shotley Bridge along the western bank

of the Derwent.

This road saw the regeneration of the

hamlet at Rowlands Gill, with the

settlement developing as a village

around the toll house, a few farm

cottages, the Towneley Arms public

house and the Road Bridge that joined

the Turn¬pike to the Gibside estate on

the eastern bank of the river. In

previous centuries the Towneley Arms

had started life as a drovers inn for

cattlemen using the Cowford across the

Der¬went where the bridge now stands.

When a wagonway was built from

Burnopfield to take coal from Pontop

to Derwent¬haugh in 1739, wooden rails

crossed the river by means of a wooden

bridge. As the bridge stood at the

bottom of a steep incline, which was

difficult to negotiate, accidents were

not uncommon, and the Towneley Arms

provided a welcome respite for the

wagoners. This wagonway was joined to

a branch from Garesfield Colliery at

Lockhaugh in 1800, but the lines

between Lockhaugh and Burnopfield were

lifted in 1810 leaving Rowlands Gill

in rural tranquility.

In 1835, the year the turnpike road

was opened, the Newcas¬tle to Carlisle

Railway began its operations. By the

1860s the railway, now part of the

North Eastern Railway, had opened a

branch line up the Derwent Valley from

Blaydon to Con¬sett. To avoid the

lands of the Gobside Estate the line

was car¬ried over the Derwent by two

viaducts, one at Lockhaugh and the

other at Friarside. This took the

railway into Rowlands Gill. With the

arrival of this railway Rowlands Gill

grew into a small town, as factories

were built to take advantage of the

high quality coal produced by local

collieries.

The setting of Rowlands Gill in the

wooded valley of the Derwent, with

frequent trains from Tyneside, made it

an ideal spot for members of the

professional and managerial classes to

live, commuting daily to and from

their works, shops or of¬fices. The

place grew very quickly, enjoying a

building boom around the turn of the

century.

|

|

Rowlands Gill; 'The Bottoms' 1908.

These houses were built for the families of workers at the Lilley Drift mine by the Priest man Colliery Co. Constructed in the early years of the century, when the demand for coal was great, they were in every way superior to the back to back pit rows of earlier years. This improvement in housing was meant to attract miners to the Lilley Drift as competition for men increased between collieries as the demand for, and price of, coal rose. This area of Rowlands Gill was always known locally as 'The Bottoms'. The postal address celebrated an incident that occurred while they were being built during the Boer War. The official name was Mafeking. The Jingoistic mood of the nation, caught here in a street name, evaporated in the horrors of trench warfare during the Great War. No one named streets after the Somme!

Rowlands Gill; Mafeking c191O, pictured above on the right. This view of the 'Bottoms' was taken looking east from the road bridge across the Derwent. The foreground trees are growing on the river bank. This view, gives a good impression of the size of Mafeking. Like most pit villages it appears to have been put up in the middle of a field. Behind the houses is a tree covered area, typical of the Derwent Valley as it has been for centuries. In ancient times woodlands such as these covered the north bank of the river from Axwell, stretching up toward Winlaton and Barlow, then continuing across to the half dozen farms of Chopwell township and on across the high ground to Allandale.

This was the area where children were warned that the witches lived. Such a belief was cultivated in medieval times by charcoal burners and iron smelters who dwelt in the woods. They surrounded their crafts with mystery and hints of magic, to keep their trade secrets safe.

|

|

Lockhaugh Viaduct

This railway viaduct is sited at a curve of the river and was built as part of the Consett Branch of the North Eastern railway. Originally a single line, it was widened to take a double track in 1905-08. Built mostly of sandstone with bricks beneath the nine arches it is 500 feet long and 80 feet above the river.

There is a deep cutting, 60 feet in depth and half a mile long, west of the viaduct at Lockhaugh and together these features form an attractive part of the Derwent Walk. From the viaduct's heights spectacular views are obtainable of the Gibside Estate to the southwest. The house and grounds there were created by coal owner George Bowes whose father had inherited the estate. Tree planting, a chapel, stables, an orangery and banqueting hall were all George's developments as was the most prominent feature to be seen from the viaduct, the statue of British Liberty on the hillside opposite. The monument is 140 foot high and topped by a 12 foot statue of a lady carved in situ with a protective shed around it, it cost about £2000 in all in 1757. The trees on either side of the valley here are particularly pleasing in autumn. Bird watcher's use the viaduct as a vantage point from which to look out for the red kites which have recently been introduced into the valley. Recent publicity material refers to the bridge as the Nine Arches Viaduct.

The viaduct near Friarside cl900 pictured above on the right.

When the North-Eastern Railway built the Derwent Valley branch line, they were refused wayleave through the Gibside Estate. This meant that the line, which ran for most of its length on the south-east bank of the river, had to cross over the Derwent to avoid the estate. The viaducts at Lockhaugh between Rowlands Gill and Winlaton Mill were therefore built to bridge the river and thus carry the line around the boundaries of the estate. This structure stands a few hundred yards upstream from Cowford Bridge. It took the line out of Rowlands Gill and across the Derwent into an estate next to Gibside that used to belong to the church. In the days before the Reformation the rents of this estate were used to support a chantry chapel and a hospital. The hospital was a building in which pilgrims could stay overnight. It was run by one monk.

|

|

Rowlands Gill; the toll house c1900.

When the Turnpike Company opened the new road in 1835, they erected turnpikes at intervals, which would only be opened to allow traffic to pass when the appropriate toll had been paid, In some places a suitable house was already available for the turnpike keeper, who had the job of colleering the tolls every day while the road was open. However, when Rowlands Gill was chosen as a tollgate site, in order to make sure traffic crossing the Derwent paid its way on joining the turnpike, it was necessary to purpose build a house. The architecture reflects the Georgian period, and the high quality stonework projects the solid and reliable image that the Turnpike Company chose to adopt. The going rates during the half century the toll was charged varied from a halfpenny for a pedestrian to two shillings for a coach and six horses. The toll was removed in 1888, when the house became the private residence of the Robinsons.

From this viewpoint, above on the right, it is possible to see the upper storey of the stationmaster's house behind and to the right of the toll house. The terrace on the right, seen from the back, was built originally for farm labourers in the late 18th and early 19th cen¬turies. This terrace, which included the first Towneley Arms public house, was almost all there was of a village at Rowlands Gill before 1835. Then the toll house was built to serve the newly opened turnpike road to Shotley Bridge. The children playing on the road are a reminder that the pace of life was less hectic than today. On the roads traffic was mainly horse-drawn and slow. People then hadn't time, energy or money to travel far. Work was hard and the hours long with few labour saving devices at home or down the mine.

|

|

Rowlands Gill; first Wesleyan Chapel l900.

This chapel was opened on 31st December 1899. Previous to this the Wesleyans had met, first in members houses, then, as numbers increased, in the station waiting room. When this proved inconvenient the Priestman Coal Co. loaned them a building at the Lilley Drift until they were able to build this chapel. It had two rooms, the main room was the church and the small room behind it was a vestry. The growing population, and successful missions, made this chapel too small from the day it opened. Foundations for the present chapel, which was built in the field to the left, were laid in 1901. From the opening of the present chapel in 1902, this building was used as a school room. Following Methodist Union in 1932 and a decline in churchgoing after the Second World War, the congregations of this chapel and the P.M. chapels came together on this site. In 1957 this building was demolished and a new schoolroom built further back from the road. This development gave the chapel a car park.

Rowlands Gill, St. Barnabas Church c1925.

This church, pictured above on the right, a wooden walled building, was erected at the beginning of the century to cater for the spiritual needs of Anglicans moving into Rowlands Gill. It served the Town in this form for over fifty years, being consecrated in 1904. It was replaced in 1956 with a modern brick church. The need for a church became pressing around the turn of the century. This was due to a large influx of people into the town, following a house building boom. Pit rows for the Lilley Drift were built at Mafeking. Stone houses for Younger's quarrymen were erected in the ravine to the west of the town. In addition houses were built on fields that had been part of Smailes Farm. All the building on the Smailes Estate was controlled by mutual covenants, drawn up with the concept of the 'Garden City' in mind. These covenants banned any alehouses or inns, offensive businesses such as chemical works or slaughterhouses and, in addition, they limited the nurnber of pigs that any householder could keep to two.

|

|

Friarside Estate; chapel ruins.

The Saxon Church in Northumbria was organised around monastic houses, such as the one at Jarrow made famous as the home of the Venerable Bede. From these monasteries was set up a network of hospitals along the main lines of communication in the Kingdom, which were the rivers. These hospitals were built about a day's journey from each other. They were often manned by a single monk, who provided hospitality to travellers and served the spiritual needs of neighbouring hamlets as required. Friarside was such a hospital for pilgrims travelling between Jarrow and Blanchland. The monk here was en¬joined to keep a lamp burning at night to guide travellers to safety. Often, as here where the estate owned 27 acres, a local benefactor would endow the place with enough land to keep the monk and build a chantry chapel in which the monk could pray for the soul of the founder. The 12th century chapel ruins, are a mile from Rowlands Gill.

Hollingside Hall

This ruin is all that remains of the fortified manor house pictured above on the right, which was the ances¬tral home of the Hardings. The ruin stands on the raised banks of the Derwent opposite to Winlaton Mill, and the ancient Harding estate bordered onto Gibside. The Harding family were renowned in the district for their bodily stature, and were known as the 'giants of Hollingside'. From 1318 their estate mill stood on the Derwent, just opposite the farms that then formed Huntleyshaugh. By the beginning of the 17th cen¬tury the Harding family fortune had changed, and they sold the estate to Gibside, becoming innkeepers and later workers in Crowleys factory at Winlaton Mill. The Harding arms were displayed for many years at what is now the Golden Lion public house, which they bought when they sold the estate. Today the fields that were once Harding land form the home of Whickham Golf Club, which has adopted as its badge the image of the old ruined manor house.

|

|

In 1867 a Methodist Chapel was opened at the western end of Glossop Street. It was here that the children of High Spen first received their education. The Marquis of Bute, who owned the Spen colliery donated £10 per year to help pay for a teacher. He also allowed Mr. Andrew Eltringham, the colliery clerk, being good at figures to do some teaching at the school.

In 1875, Mr. Thomas Armstrong became Head Teacher and remained so till after the new board school was opened in 1894. His salary then was £30 per term and he had six pupil-teachers under him! Four of these were his own children who, having left school as pupils, returned as trainee-teachers. The wages of the teachers in the early days came from a levy of 1d a week per child. Sometimes the pit was working short-time, so the miners didn't pay their levy, much to the exasperation of the Headmaster. Inspectors visited the school annually and tested the children on their knowledge. Payments to the teachers were on results, so some teachers flogged the children in their efforts to instil learning into them. Many teachers must have been on the bread-line!!

In 1870 the first Education Act was passed. School Boards were elected and in 1876, the power to enforce compulsory attendance became general and the leaving age was raised from 13 to 14. It was not till 1894 however that High Spen got its own Board School, for by this time the Chapel building was unable to cope with all the pupils registered in it. The school still stands today and is used as a Junior School. For many years the Board School was controlled by Mr. Coulson, a stern Headmaster. He died in 1931 and a plaque was erected in his memory, in St. Patrick's Church by the British Legion. He was succeeded by Mr. Davidson who will be remembered by many of those still living in the area. On his staff were Mr. Robert Emmerson (a war-time hero) Mr. Newark Smith, Mr. Waters, Mr. Colling and Miss (Ganny) Hind.

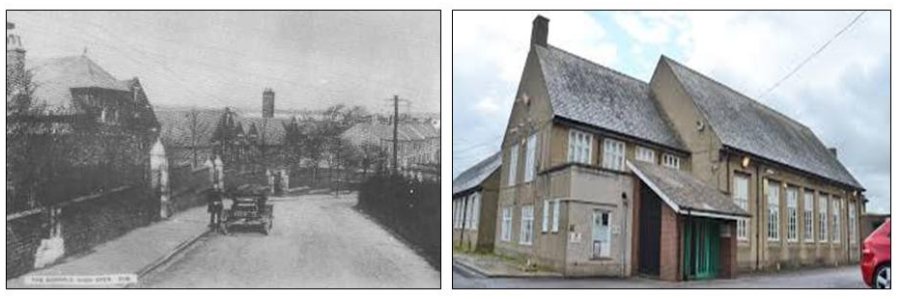

Hookergate Grammar School

In 1933 Hookergate Grammar School pictured above on the right, was built on a very open country site about a mile and a half west of the village, and children by that time were conveyed up there by bus. Many children from this area have always travelled to Newcastle secondary schools by train and later by bus.

It was a secondary school and sixth form located in High Spen in the Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead, England.

The school was formally merged with Ryton Comprehensive School in 2011, and was renamed Charles Thorp Comprehensive School (now Thorp Academy). The new school operated over both of the former school sites until 2012 when the school relocated completely to the former Ryton school campus.

The site upon where the school was located had been used for filming of BBC Children programs such as Wolf blood and an off take of Tracy Beaker however the school campus is now no longer required and has been put for sale for development.

|

|

Highfield: Whinfield Coke Works

Coal has been mined in England since Roman times, and between 8,000 and 10,000 coal industry sites of all dates up to the collieries of post-war nationalisation are estimated to survive in England. Three hundred and four coal industry sites, representing approximately 3% of the estimated national archaeological resource for the industry, have been identified as being of national importance. This selection, compiled and assessed through a comprehensive survey of the coal industry, is designed to represent the industry's chronological depth, technological breadth and regional diversity. Coking is the process by which coal is heated or part burnt to remove volatile impurities and leave lumps of carbon known as coke. Originally this was conducted in open heaps, sometimes arranged on stone bases, but from the mid- 18th century purpose built ovens were employed. By the mid-19th century two main forms of coking oven had developed, the beehive and long oven, which are thought to have been operationally similar, differing only in shape. Coke ovens were typically built as long banks with many tens of ovens arranged in single or back to back rows, although stand alone ovens and short banks are also known. They typically survive as stone or brick structures, but earth covered examples also exist. Later examples may also include remains of associated chimneys, condensers and tanks used to collect by-products. Coke ovens are most frequently found directly associated with coal mining sites, although they also occur at ironworks or next to transport features such as canal basins. Coal occurs in significant deposits throughout large parts of England and this has given rise to a variety of coalfields extending from the north of England to the Kent coast. Each region has its own history of exploitation, and characteristic sites range from the small, compact collieries of north Somerset to the large, intensive units of the north east. All surviving pre- 1815 ovens are considered to be of national importance and merit protection, as do all surviving examples of later non-beehive ovens. The survival of beehive ovens is more common nationally and a selection of the better preserved examples demonstrating the range of organisational layouts and regional spread is considered to merit protection.

Whinfield Coke Works were built around 1900 to power Victoria Garesfield Colliery and to light Whinfield Cokeworks and the streets of Victoria Garesfield, Highfield and Rowlands Gill. It later powered an alloy factory adjacent to the cokeworks and when this was greatly enlarged during World War One, the power station was enlarged too. After the War the alloy factory closed and the surplus power from Whinfield Power Station was sold to NESCO, the Newcastle Electric Supply Company. The power station closed in 1932.

The remaining Whinfield beehive coke ovens survive particularly well and represent a rare example of intact beehive ovens, a design pioneered within the Durham coalfield. The structure of the ovens includes many original features which illustrate the technology employed in a large scale commercial coke works from the mid-19th century to the late 1950s. In addition, the site represents part of the last beehive coke works to be operated in Britain.

Crowley’s Iron Works pictured above on the right.

Ambrose Crowley originally a Quaker from Stourbridge was the son of a successful ironware maker and trader and was apprenticed to an ironmonger in London, soon setting up in business for himself. After an early venture at Sunderland he moved in 1691 to Winlaton, later establishing works at both Winlaton Mill and Swalwell (in 1707). Water from the Derwent was used in tempering steel and the river itself for navigation purposes using keelboats giving access to the factory.

Nails, pots and pans, canon, anchors, chains and swords were among the products of the 3 factories, Swalwell generally producing the heavier items. The firm had its own ships and though the business was run from Greenwich, London, day to day operations were administered through local committees.

A system of social welfare provided sick pay, unemployment benefits, pensions and funeral payments, as well as schooling for workers’ children, a minister and medical services. Disputes were settled by Crowley ‘Courts’ in accordance with the firms’ Rule Book. After Crowleys death in 1713 the firm continued to be run by the family, eventually becoming Crowley Millington’s and passing to various owners, closing in 1863 when they were in the possession of a Mr Laycock who eventually reopened the works which continued until 1911. The firm declined as a result of competition from other iron and steel centres using more advanced techniques.

The Northumberland Paper Mill took over part of the site from 1887 to 1909 and their tall chimney still stands as a record of their presence in Swalwell. General Concrete Products occupied Crowley’s site after the war-later Bespoke Concrete Products and then the site was cleared.

In the early 1700s, Sir Ambrose Crowley's Iron Works at Swalwell were considered to be the biggest in Europe. The works were a major supplier of materials' to the Admiralty as well as shipping many items to the colonies. They were also one of the first works to produce steel.

The works were considered to be of such importance that in 2005, a team of archaeologists from Pre-Construct Archaeology conducted an excavation on the site currently occupied by Lidl Supermarket. The purpose of the excavation was to unearth and record the foundations of part of the old ironworks which had been built in Swalwell around 1707. More about the works can be read in 'Men of Iron: The Crowleys in the Early Iron Industry'. The team meticulously measured the site over a period of months and I was fortunate enough to be granted access to take photographs, some of which are shown below.

Sadly the foundations were covered over and Lidl's' was subsequently built on the site.

|

|

Winlaton Mill; the Golden Lion inn.

The small cottages in front and to the right of the Golden Lion inn formed, with the pub, the Low Close area of the village. The pub was originally Huntley Hall, which had given its name to the village for centuries before Crowley built his iron mills. There had been a flour mill at 'Huntley Haugh', owned by the Prince Bishop, since the early years of the 14th century. Some years later the mill's energy was also put to use in the fulling of wool. By 1632 the Hardings of Hollingside had acquired the mill and the hall, which became an inn. It was then known as the Three Golden Greyhounds. These greyhounds were on the arms of the Harding family, and were painted on the inn sign. When Crowley built his works at Winlaton Mill in 1691, his employees were for¬bidden to frequent it, or any other alehouse.

Now renamed ‘The Red Kite’ the pub is reputed to exhibit ghostly manifestations. these include a number of male ghosts from olden days. A photograph taken in this pub appears to show a middle-aged man sitting in the background, slightly out of proportion to the rest of the bar room. It is believed that this is the ghost of one of the men killed at the nearby forge.

13. Rowlands Gill; Towneley Arms inn pictured above on the right.

The Towneley Arms, Rowlands Gill's only public house, was opened in 1835 to serve travellers (and their horses) using the new turnpike road between Swalwell Bridge and Shotley Bridge. At that time the pub and the nearby Toll Gate were the only buildings in what is now Rowlands Gill (apart from a couple of farms). Already a tied house belonging to Aichies Breweries, and the houses that formed the hamlet of Rowlands Gill in the days before either the turnpike or the railway reached here. It developed as a post inn with the coming of the turnpike, when it was increased in size as extra rooms were built out in a gable at the back. It started trading as a public house by serving travellers using the ford (later Derwent Bridge) at Cowford with food and home brewed beer in its front parlour. Its closeness to the railway station ensured its future and a place in folklore as the pub in which 'War Nanny' drank so much gin that she 'missed the train'. This exploit was the subject of the song 'War Nanny's a Maizer', popular 100 years ago in Newcastle's Music Halls. Today's Towneley Arms Hotel replaces the old street.

The original Towneley Arms served the village until 1961 when it was demolished and replaced by a much larger building - the new Towneley Arms. The old building lasted some 126 years, but sadly the "new" Towneley Arms was much more short-lived - it closed in May 2000 and has since been demolished.

|

|

Post Office

In 1896 Rowlands Gill did not have a post office at all – the letters for Rowlands Gill were probably still delivered by Winlaton postmen. But in 1897 the first shop in the village was built on Station Road (now called Burnopfield Road) and it became a post office and grocery shop. Miss Annie Lundy was the sub-postmistress in charge; she had been running Victoria Garesfield Post Office before she moved to Rowlands Gill.

Miss Lundy did not stay very long and in 1904 she was replaced by Mr Joseph Lumley who came from Stanley – Mr Lumley’s nearby drapery shop then became the village’s second post office, pictured above on the left. His shop and the shop next door had been built in 1902 by Mr Thomas Usher. Mr Usher ran a grocery business in one and Mr Lumley ran his drapery business (and now his post office) in the other. At first Mr Lumley rented the shop from Mr Usher, but the first two post offices in Rowlands Gill were very close to the railway station. This was very useful because letters were brought to the village by train. There can be little doubt that the postal service then was much better than it is today. he later bought it.

Mr Joseph Lumley gave up the post office in February 1949 after running it for nearly 45 years. Sadly he died a few days later. The drapery and newsagents business was carried on by a relative. Rowlands Gill needed a new post office and a new sub-postmaster.

In April 1987, after almost 90 years, Rowlands Gill Post Office stopped sorting letters for the village. Letters were to be sorted at Blaydon instead and the village’s postmen and postwomen had to collect their letters from there. There must be a sensible reason for doing this but, to many, it seemed very silly – the postmen and postwomen used to collect their letters from the village post office now they would have to travel to Blaydon and then back to Rowlands Gill.

“The Grove Temperance Bar” was owned by Mr Thomas Carrick Middleton, an accountant, and his wife, Josephine. This shop had been built in 1924 for Miss Ethel and Miss Amelia Gibson and they sold sweets and ice cream from the shop until October 1945 when they sold it to the Middletons. The G.P.O. decided that Mr Middleton should be the new sub-postmaster and “The Grove Temperance Bar” should become the new post office. An extra room was built on the side of the shop; this was to be the sorting office, the place where the postmen sorted letters and parcels. At first they continued selling sweets but later changed to cards and stationery. The new post office was given the same telephone number as the old one -Rowlands Gill 361.

Mr Middleton senior died on 26th July 1992 and Terry, his son, took over as sub-postmaster. Unfortunately over the next ten years or so the post office was subject to series of armed raids which left Mr Middleton injured and very lucky to be alive. There was even an attempt to kidnap him. Mr Middleton was rightly praised for his bravery in tackling the would-be robbers and assailants, but understandably he became increasingly concerned for the safety of his family, his staff, and himself. As a result, in 2004, Mr Middleton decided to close his post office and retire. A new post office was opened a few months later in the newsagents shop around the corner, a shop which, ironically, had once belonged to the Lumley family who had run the village’s 2nd and 3rd post offices.

Rowlands Gill; the Co-operative Store.

The Rowlands Gill Co-op was a branch of the Burnopfield Co¬operative Wholesale Society. These C.W.S.s were based on the concept of selling goods, often produced in Co-op factories at Pelaw or Manchester, directly to members, thus cutting out any middleman profit. After all expenses incurred in running the Society had been paid, any surplus was distributed to members quarterly as a percentage dividend on each member's spending. On the ground floor were the various 'departments', or shops. The upper storey of the building had a Hall, reading room and committee rooms for the use of members. Here at Rowlands Gill one of the committee rooms was used as a Labour Exchange. In front of the store several of the unemployed of the town sit or stand around while waiting for the 'Dole Office', as the Labour Exchange was known, to open.

A 1960 picture of Station Road is above on the right, the shop on the left, which is now the Halifax Building Society, was the Co-op Butcher's shop run by Eric Hopper. Eric, who was himself a keen photographer, lived further along Station Road with his wife Edith and children Kenneth, Trevor and Patricia. The shop on the right, which is now Flower Design, was the Co-op Chemist's shop run by Joseph Clark. Joseph, who was confined to a wheelchair, lived above and behind the shop with his wife Maud and sons Leslie and John.

|

|

Stella Hall

Stella Hall pictured above on the left, was a large building, essentially Elizabethan in character, but with an 18th-century south front. Older sections showed mullioned windows and other Elizabethan architectural features whilst the 18th century windows and south front were the work of the architect James Paine, designer of Axwell Hall on the other side of the district. The Hall, Drawing Room and library were of Paine's design but the former Roman Catholic Chapel was older.

Stella Hall has had a long history that goes back as far as 1143 when there was a nunnery on this site. The present house was built by the Tempest family, Newcastle merchants. They occupied Stella Hall for 150 years and then in 1700 it passed into the ownership (by marriage) of Lord Widdrington, a noted Jacobite. Widdrington, on 6 October 1715, invited his friends and tenants to breakfast at the hall and, after toasting the Stuarts, they all set off to join the Earl of Derwentwater and his rebels. The uprising failed and Widdrington was sentenced to death though he was later reprieved and his estate and house restored to him.

In later years Garibaldi and Kossuth were among the famous people who were entertained at Stella Hall. A statue of Garibaldi was discovered some years ago in the garden of a house on the estate and the head can now be found in the entrance lobby of Blaydon library. In more modern times the hall became the home of Joseph Cowen, M.P. and owner of the Newcastle Daily Chronicle who died in 1899. The last member of this family, Jane Cowen, died in 1948 and the house was demolished in 1953.

The remaining parts of Stella Hall, now known as Stella Hall Cottage, is a listed building.

Axwell Hall

Axwell Hall above on the right, a Grade 2 listed building, still exists intact and has an imposing appearance from the outside but it stands empty now, awaiting conversion to luxury private residences - this work is now underway. It has to be the finest building still standing in the Blaydon area, with the demise of Stella Hall in the 1950s.

In those days everyone in the Blaydon area referred to 'the bad lads school' but its proper name is Axwell Hall (or Axwell House) and it is situated just east of Blaydon/Winlaton in lush woodland which descends down to the River Derwent.

Its history goes back to the Clavering family. They were land and mine owning gentry who were decreed a baronetcy 'Clavering of Axwell' in 1661, following the restoration of the monarchy. The family descended from 13th century Anglo-Norman nobility, the Lords of Clavering and Warkworth, from Alan de Clavering of Callaly Castle who passed away in 1328. Northumbrian branches of the family include Axwell, Callaly, Duddo, Berrington and Chopwell. Inter marriage also led to the Clavering-Cowper family.

It was in fact the grandson, merchant adventurer Sir James Clavering, who became the first Baronet in the family. He was Mayor of Newcastle and he purchased the Axwell Park estate in 1629 for £1700. An early manor house on the site was eventually demolished in 1758 by his descendant Sir Thomas Clavering, who replaced the house with a substantial mansion and assisted eminent architect James Paine (1712–1789) in the Palladian design of the new house. James Paine carried out some work on Stella Hall too.

|

|

Clockburn Drift

Clockburn Drift near Winlaton Mill actually opened in 1952, and provided an outlet for coal from Marley Hill pit to which it was connected by tunnel.

A double track 3ft 6in (1,067 mm) gauge railway crossed the River Derwent on a girder bridge just outside the mine entrance. Coal was then transferred to standard gauge wagons and transported on to the Derwenthaugh Coke Ovens in standard gauge hopper wagons.

There were extensive sidings here and Derwenthaugh cokeworks were nearby. The coal wagons were taken to the nearby Derwenthaugh Staithes.

The Drift closed in 1983 as did Marley Hill Colliery

Axwell Park Colliery, pictured above on the right.

Opened/Sunk: 1841, flooded soon after, re-opened 1889. On December 14th 1903 OPC bought Axwell Park Colliery (also called Axwell Garesfield Colliery) and, on the same date, changed the name of the Company to Priestman Collieries Ltd. (PCL). There was some generating plant at Axwell and it was proposed that PPC should take over this plant and extend it. Merz and McLellan were consulted and thought it not to be worthwhile, so the idea was dropped. Axwell Park Colliery was supplied from the Blaydon Power Station/NESCO network by means of a CDEPDC cable along NER's Newcastle to Consett railway. A 1000 kW substation was installed at the colliery. Axwell Park Colliery became one of the most up to date collieries in the country and, like Victoria Garesfield, it used electricity to provide all its motive power.

Axwell Park Colliery closed in 1955

|

|

Hikey Bridge pictured above on the left.

The footbridge at Swalwell is known locally as the Hikey Bridge, probably because it moves or sways when someone crosses. It is sometimes called the Sands Bridge. It is a suspension bridge erected in 1902 by D Rowell of Willesden, London to provide access between the allotments which once existed on both sides of the river. Suspended on wire ropes slung from steel towers, it has a timber deck of width 5 feet and a span of 121 feet. An earlier bridge existed at this site as evidenced by a stone abutment nearby and is shown on the 1867 Ordnance Survey map, and a ford was just to the west. The cables were renewed in 1925.

Although most of the allotments or 'gardens' have gone, the bridge still gives access to those remaining, and links the cycle/pedestrian paths on either side of the Derwent. The embankment carrying the A1 Western By-Pass intrudes to the northeast of the bridge, but otherwise trees and grass line the banks at this spot with views of the old railway bridge to the west, and the tall factory chimney, a Swalwell landmark, is to the southeast while swans are often seen swimming nearby.

Old Swalwell Bridge pictured above on the right.

This is one of the Derwent's older bridges, dating from about 1760, when an advertisement inviting tenders for its construction appeared in the Newcastle Courant. Built by the Clavering family of local landowners who lived in nearby Axwell Hall, it carried the main turnpike road from Gateshead to Hexham over the Derwent until it became inadequate for 20th century traffic and a new bridge was built 100 yards to the west. Only 16 feet wide it has three arches and cutwaters which serve to break up and divide the current and prevent damage to the structure from debris carried down the river at time of flood. It is Grade Two listed. A gas main on the east side of the bridge deck was removed in 2015 and the surface given new tarmac.

On the east side is an aquaduct in stone and with lattice girders carrying a cast iron/steel water pipe fed from Benwell reservoir carrying water to a pumping station in Gateshead which supplies that town. This somewhat spoils the appearance of the bridge when viewed from upstream to the west but sand blasting and re-painting in 2015 have improved the appearance. On the south side is the old toll house, still inhabited and known as Bridge End Cottage, and it is Swalwell's second oldest building after the former Angel Inn.

The bridge is used by pedestrians and cyclists to provide access from Swalwell to the Derwent Park or to Derwenthaugh via paths on the north side of the river. A few vehicles still cross to a garage on the north side where once a smithy existed. The river banks are wooded from here virtually to the river's source and, like the Hikey Bridge downstream, there are good views of the former railway bridge from the old stone parapets. An old postcard from the early days of buses shows one of these vehicles dangling precariously over the bridge having crashed through a parapet. A level crossing once existed just to the north of the bridge, over which ran the 'Main Way' coal-carrying railway from northwest Durham pits to Derwenthaugh.

|

|

Path Head Mill

Water power was the main source of energy for many years and streams powered all sorts of machinery. Mills were used for wool (washing, spinning and weaving), the manufacture of paper, snuff and gunpowder,sawing timber and the generating of electricity. Many mills lasted into the industrial revolution but subsequently went into decline.

Recently, there has been renewed interest in water mills and enthusiasts have saved many from total decay. A few mills have been restored to working order and enjoy a new lease of life. For many years the site of Path Head was neglected. Considerable time was spent on excavating the derelict site before restoration work could commence.

The Mill's History

Started in 1730 by the Townley family, the Path Head Mill worked as a corn mill until 1828. During its working life it changed owners to the Cowen family. Around 1974 the farm buildings became derelict, of which the later 1930's farmhouse is the only survivor. The area was then surrounded by extensive gravel extraction and only poultry survived. Evidence of vehicles was found during the excavations around the mill building.

The mill pond was choked with fallen willow trees and these were removed to clear access to the building and the pond. The old corn stack terraces had their dry stone walls repaired and a pole barn was erected to cover some of our engineering artefacts.

Lintzford.

This hamlet lies about 2 miles south of Rowlands Gill, where the river is spanned by a very old single arch bridge, probably dating from the middle of the 17th century when a Corn Mill functioned there. The Richardson Printing Ink Co. holds parchment deeds complete with wax seals, some written in Latin, for the Corn Mill and land, pictured above on the right, dated 1695.

Ninety years later the Annandales took over the Corn Mill and ran it as a paper mill until 1912. They built Lintzford House in 1790, but recent alterations have uncovered an example of dragon-wing roofing, which may be of an earlier period. This house including recent extensions by the river is listed as an ancient monument. From 1912 - 1922 Charles Marsden ran the paper mill then in 1923 the present owners converted it into a printing ink factory with world wide trade, agencies in many countries, and also three factories in India.

In the garden adjoining the factory are relics such as grindstones from the corn mill, an Elizabethan stone urn, and a boundary stone, marked with an Elizabethan E. Over the river from the dam is a row of cottages due for demolition, - and they must have been converted from an old inn which once stood by the roadside near to the old ford. It is thought there must have been a Pilgrim Way from Jarrow to Blanchland Abbey via Friarside Hospice, and Lintzford, as a very old blacksmith's forge has been discovered in a remote part of the ink works.

Excepting Lintzford Farm owned by the Lawrence family, all the property and houses belong to the Richardson Printing Ink Co. The inkworks was taken over by Dufay Paints in 1966 and it finally closed in 1987. The premises have since been converted into flats.

|

|

Ryton House

A curious house with seemingly little known history. Ryton was an 18th century building of brick, the main front of two storeys, the sides of three, in an awkward juxtaposition, shown Clearly in the somewhat naive engraving by Boniface Muss. At the corner was a confusion of Venetian doors and windows and a lunette, at different levels. In the 19th century a bay-window was bullt out at the side. In one room the Ryton Petty Sessions were held.

To the side of the house was the stable block, with a tall entrance-arch and facade, an interesting essay in 18th ctmtury Gothick, with battlements, cross¬slits and panels of quatrefoils and loz¬enges, symmetrical but very elementary. The house was latterly a Conservative club; amazingly, and somewhat grotes¬quely, the main entrance was covered by a shallow greenhouse (it could not be dignified with the name conservatory).

Ryton House, which stood south of the church, was demolished in the 1960's and replaced by an estate of houses. Ryton was the seat of the Humble family in the 18th century. Joseph Lamb (d. 1800) married the Humble heiress, and their son Humble Lamb (d. 1844) inherited the estate. He was succeeded by his son Joseph Chatto Lamb (1803-84) and grandson Joseph Lamb.

Winlaton Hall pictured above on the right.

Once a seat of the Roman Catholic Hodgsons of Hebburn, Winlaton Hall passed c.1700 to Sir William Blackett, who leased it to Sir Ambose Crowley, Tyneside industrialist (d.l713). In 1704 Crowley used the Hall as a chapel, later as a house, offices and warehouse. It was vacated in 1753. Crowley probably added the curious facade of battlemented corner-towers with a Dutch gable between. An inscribed gable stone read "Crowley and Belts Castle 1864" (Two Belt sisters sold provisions in part of it c.1830). Part of the Hall in domestic use was described as "well-situated, fit for a gentleman's family ... with several houses and smith's shops." Joseph Laycock came to Win¬laton in the early 18th century to manage Crowley's works. His grandson Joseph Laycock (1798-1881) rebuilt the residen¬tial part of the Hall c.1835, but later moved to Low Gosforth House. In 1896 the Hall was the seat of H. W. Grace; it was later owned by Matthew Kirsop, but was demolished in 1928.

|

|

Highfield; Smailes Farm cl930, pictured above on the left.

Smailes Farm was built in the 18th century. The name Smailes, originally 'Smeales' meaning 'Narrow', is first recorded at this location in Bishop Pudsey's tax Survey of 1183. Smailes Farm appears in records in the 17th century and was one of the farms which formed, with the Towneley Arms, the rather sparsely settled and well¬ dispersed hamlet of Rowlands Gill in the years before the turnpike and railway enabled the town to grow. Christopher Hopper of Coalburns spent his honeymoon at Smailes Farm. Hopper, who began his working life as a wagonway horseman, was an early con¬vert to John Wesley's Methodism. In 1744 he became one of the first local preachers. Within a year of beginning to preach he was arrested. He claimed: 'My crime was to tell of the judgement that awaited all sinners.' The Rector of Whickham said the offence was 'preaching without a licence'. On Wesley's death in 1791 Christopher Hopper succeeded him as President of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference.

The tranquility of this scene, with the cows being taken for milking, belies the hard lives that faced most workers, whether on the land or down the mines. For the farm hand days began at sun up, and lasted till sunset. If it rained, they couldn't work in the fields and were not paid. For the miners the shifts only started when they had walked from the pit shaft to the coalface, and if they hit stone or shale their earnings fell. These were the days when families were evicted from the tied cottages of the farms or the collieries if the breadwinner fell sick or died. Due to frequent lay-offs or poor harvests, few ordinary folk had the chance to save, so if they survived fever epidemics or industrial illnesses, many had only the Workhouse to look to in old age.

Low Spen; farm cl930, pictured above on the right.

This building, built originally as a farmhouse, was substantially rebuilt in the reign of Queen Victoria as a barn. During the present century its main use has been as a grain store. Today it is being restored as a private house, 'The Granary'. One notable visitor to the old farmhouse was John Wesley, invited there in 1744 by the farmer, John Brown. Subsequently the farm became a regular meeting house for a group of local 'Methodists', the nickname given to Wesley's followers. Christopher Hopper was converted here while listening to a sermon on 'faith, hope and charity', by Mr. Reeve, one of Wesley's first local preachers. John Brown continued in the faith for the rest of his long life, welcoming worshippers to Sunday meetings in the farm until his death in 1808. John Brown witnessed the early days of persecutions, including the arrest of Hopper, but lived to see the expansion of the new church, when there was a Wesleyan chapel built or planned in almost every village.

|

|

Lintz Green Railway Station was on the Derwent Valley Railway Branch of the North Eastern Railway near Consett,Durham, England. The railway station opened with the rest of the line on 2 December 1867 and closed 2 November 1953. The station is now part of the Derwent Walk Country Park.

The station was infamous at the time for the unsolved 1911 murder of its stationmaster.

On the night of Saturday 7 October 1911 the sixty-year-old stationmaster, Joseph Wilson, was shot when returning home after closing his office at the station. Although he did not die instantly, when questioned, Wilson was unable to communicate who had shot him.

The motive for the killing was probably robbery as Wilson was in the habit of carrying the day's takings from the booking office to his house, a trip of 50 yards, when he left for the night. On the day in question, however, he had transported the money earlier in the day.

Although the murder hunt, still one of the largest in the North East, involved two hundred officers nobody was convicted of the crime.

The prime suspect was the relief porter Samuel Atkinson who was arraigned at the local Magistrates' Court for the murder and sent for trial at the Assize Court in Durham. At the opening of the trial the local Chief Constable William E Morant appeared and offered no evidence against Atkinson, who was released.

Stirling Lane (formerly Smailes Lane) pictured above on the right.

On Thursday, 1st November, 1855, Dr. Robert Stirling left the surgery at Burnopfield where he was employed, to visit patients at Garesfield and Spen. He was a native of Kirkintilloch, eight miles from Glasgow He had studied at Glasgow University, and was working with Dr. William Henry Watson as his assistant, to gain some experience before joining the Turkish army as a doctor in the Crimea. He was a cheerful young man of 26, smartly dressed in a black suit, who was noted for his fast striding pace, and his habit of twirling his walking stick when on his daily rounds. He had only been in the district for ten days, but had already endeared himself to many of the patients with his friendly manner.

He completed his rounds at the home of Mrs. Corn at Low Spen. leaving there about 2 p.m. When he failed to return to the surgery, his employer became worried. The next morning he informed the police, and sent a message to Dr. Stirling's father. The police mounted a search and when Charles Stirling and another of his sons, Andrew, arrived, they too joined in the hunt, After a long search, the body of the doctor was found by his father and Thomas Holmes, a local man, in a small wood near the bottom of Smailes Lane, Rowlands Gill.

A reward of £500 (over £30,000 today) was offered for the discovery of the killer or killers. The inquest opened on Wednesday, 21st November and after two adjournments, finished on 9th January 1856. It was conducted by J.M. Favell, the coroner; also present were Mr. Hudson, deputy coroner; G.H. Ramsay, J.P. of Derwent Villa; Major White, Superintendent of Durham Rural Police; William Hutt, M.P. and R.S. Surtees of Hamsterley Hall. The jury had assembled, but the foreman, Thomas Burnett, was absent. The coroner severely censured his conduct and fined him £40 (£3,000 today). Evidence was given by Dr. Watson and one of his students, G.S. Thompson, regarding the time Dr. Stirling left the surgery - shortly after 9.30 am. Thomas Holmes told of finding the body. Then William King Eddowes, surgeon of Derwent Cote House, described the wounds on the body : gunshot wounds in the right abdomen, with a spread of shot about the size of the palm of a hand. There were knife wounds on the left side of the face, 2 inches long and 2 1/2 inches deep. The face was badly beaten, and the nose was broken.

WHISKY JACK who gave his name to a brook near the village, was a smuggler from Norfolk who roamed Scotland and the Border Country and fell in with illicit distilleries. He came to the Coquet and Tees areas, acquired a still of his own, and marketed in mines and factories. In 1885 he lived in the woods near Rowlands Gill and was tried for, and acquitted of, the murder of local Dr. Stirling. Joseph Cowen then employed him for 13 years as gardener, and he proved sober, honest, reliable, and most industrious and knowlegeable, but he eventually emigrated it is believed, to Australia, though it is reported he was seen in Kentucky. Whisky Jack was John Kane - born 1797 - and his cottage was situated where Woodside Cottage, Lintzford Road now stands. Coincidentally, one of Jack's direct descendants, who understandably wishes to remain anonymous, was very recently living within 300 yards of this location - and may well still be living there!

There were many confessions to the murder, but none were consistent with the facts. The perpetrator was never found. Smailes Lane (the section where the murder took place has since been renamed Stirling Lane)

|

|

Historic Blaydon.

The name Blaydon has Anglo Saxon origin: Blac = a name & Denu = a valley.

The first mention of Blaydon is 1256 when an entry in the Northumberland Assize Rolls mentions the Lord of the Manor of Denton complaining that Robert Neville and Everard of Blaydon had destroyed his fish weir on the Tyne. Winlaton coal is mentioned being shipped from Blaydon in 1367 and there was some sort of passenger boat “a great boat” recorded in 1593.

The first clear map of Blaydon is from an estate map dated 1632/3.Beginning at the site of the modern Swalwell Bridge then known as Selby’s Ford – there was no bridge then across the Derwent – the road from Winlaton Mill ended roughly where Swalwell roundabout is now. There was probably a footpath through the field to Derwenthaugh, although it is not marked on the map. Away to the south stood a large whitewashed mansion, known as the Whitehouse, or Winlaton Whitehouse, and it stood upon Spring Hill, about 100 yards west of the present Axwell Hall. A small wooded park of 31 acres surrounded the house. Beside the road, where the lake is now, in Axwell Park, lay a patch of marshy ground called the Black Meres – lakes or ponds.

To the north east stood Bate House which appeared to be a substantial mansion. Who Bate was and when he lived is unknown but the estate is mentioned in the sale of Winlaton manor in 1569, so presumably Bate lived here before that date. In front of the house was a park stretching across to the Derwent, the road to Scotswood Bridge cutting through the centre of it today. The two ( white painted ) cottages which have recently been renovated were probably connected with the mansion. Behind stood a large field known as Batehouse Close, which is the land on which Blaydon Comprehensive School ( now baths & health centre) stands today.

Next to Batehouse Close stood three large tracts of marshy land named the Strother, Nether Strother and Far Strother, all extending from the Hexham Road to the River Tyne. It was the home of water fowl, many of which were shot by the sporting fraternity of the neighbourhood until the turn of the 20th century. The last water rail being shot here in 1892.

Whilst Blaydon is famous worldwide for “The Blaydon Races”, it has a rich history and is regarded by many as the Capital of Gateshead.

|

|

The Spike Castle - Turret Place.

Colloquially known as The Old Castle, The Spike Castle but properly, as per old maps, Turret Place, this remarkable structure stood alongside Patterson Street on Blaydon Haughs (The Spike). With the growth of industry during the industrial revolution and particularly with the coming of the railway, Blaydon rapidly grew from a few farms and keelmen's abodes to become a fair sized industrial town including a riverside community on Blaydon Haughs about half a mile east of the main township. On Blaydon Haughs, just beyond the Factory Road/Patterson Street forked junction, was an old castle like building shown on old maps as Turret Place. Its not obvious from the images but I've been told it also had a dry moat around it.

The building's origins may go back to the land owning Selby family or it may have been built somewhat later but in a medieval castellated style. An elderly uncle of mine tells he he was told by a Spike elder, when a young boy, that it was not as old as it looked. However it was in existence and shown on maps dated 1856 - 1865.

It is thought that it was indeed built in the 1640s by the Selbys as a family home but in later years was vacated and fell into dilapidation. Local businessman Sir Joseph Cowen brought over a contingent of Irish labourers to work on the removal of Blaydon Island (one time site of the Blaydon Races) and other improvements to Tyne river depth and navigability. So around the 1870s he had the old castle building renovated, converted into several small apartments and used as a lodging house by some of these workers. As some of the Irish vacated the residences were gradually occupied by local factory workers.

The improvements to the Tyne greatly facilitated access further up river by bigger cargoe boats and this enabled much easier transportation of raw materials and finished goods produced in local factories, brickworks, mines etc. Cowen was duly knighted for his work as chairman of the Tyne Improvement Commission. Sadly this, and the growth of the local rail network, marked the end of the keelman way of life.

The old pen and ink drawing pictured above is by Jas Egen.

|

|

The Bessie Pit Blaydon Burn

First shown on the 1858 ordinance survey map as a single building with enclosures to the south-west, the pit was part of Joseph Cowen’s Blaydon Burn Colliery. The pit was taken over by Priestman Collieries c.1900 and vested with the National Coal Board Northern Division in 1947. Most of the mines in Blaydon Burn were worked for fireclay for Cowen’s Firebrick Manufactory. The entrance to the mine, now blocked, was along the railway line to the right of the picture. The structure shown was the winding house. It was closed in 1950, pictured above on the right all that remains of the Drift entrance.

The cracks and crevices in the crumbling retaining walls now provide the ideal home for pipistrelle bats, which feed on insects by night.

Blaydon Burn Nature Reserve

From the c19th industrial development expanded rapidly along the Blaydon Burn to include a number of industries related to the processing of coal. The supply of cheap local fuel and good transport links led to the development of coke works, steelworks, iron foundries and brickworks making Blaydon Burn one of the most industrialised parts of the region.

|

|

|

|

|

|