|

|

Tommy Armstrong

|

Tommy Armstrong

Since we featured the short story of

Tommy Armstrong some months ago, there

has been many enquiries from people

greatly interested in Tommy's life. As

a result of that interest we have

decided to feature this more complete

story of Tommy Armstrong.

Tommy was born in Wood Street

at Shotley Bridge County Durham on the

15th August 1848. His father and

mother

had moved to the area from Haswell.

Today he twin rows of stone-built

cottages have been demolished, as have

the gas works and flour mill which

once

operated at either end. This was the

Western fringe of the coalfield, along

which small drift mines like those at

Whittonstall and Daisy Hill worked. In

the early 1850's, Tommy's parents

moved

Eastwards once again this time to

settle in the Stanley area, first at

South Pontop and thereafter in and

around East Tanfield and Stanley. It

was a move from the countryside of the

Derwent valley to a rapidly expanding

and urban mining district. Here Tommy

started in the pits, working at the

South Pontop and East Tanfield

(pictured above) Collieries, as a

youngster he had suffered severely

from

rickets, and this illness was to leave

him deformed. His bow legs in latter

life needed the permanent aid of

sticks

and he never reached more than five

feet in height, Undoubtedly, this

affected his working life. (His son

recounts how, as a boy Tommy had to be

carried to work by his older brother,

to his first job as trapper, opening

and shutting air lock doors, a job

which he would have been able to do

with little or no walking.) Equally

clearly, this served as an important

material pressure on his song writing

career, nor was this a unique

phenomenon. George Ridley's serious

song writing was spurred by necessity

and the consequences of a severe

industrial accident. Such accidents

were not uncommon, and for working men

in the North, the popular culture of

singing, entertaining and writing

verse

offered the possibility of a small,

but

alternative income.

He married Mary Anne Hunter in 1869

and they produced 14 children,

following the death of Anne in 1898 he

married Ann Thompson in 1901

Songs were sold as broadsheets,

printed

and distributed by local printers;

funeral directors bought verses for

their cards. This was one of the ways

in which Tommy Armstrong came to earn

a

living. What put him on the way was

the

presence of a vibrant popular culture

in the Stanley area.

In his unpublished ‘History of

Stanley’

Fred Wade makes reference to the

musical evenings that took place in

the

town and to the popularity of a local

comedian called Mr. Macmillan. At the

age of fifteen Tommy attended one of

his performances in Stanley. That

night

the comic shared the bill with Joe

Wilson, a young man who was making a

name for himself as a street singer on

Tyneside, from this time on it would

seem that Tommy Armstrong was set to

become the "pitman's poet" and if this

was made possible by the popular

culture of the area, it was the mines

and the mining industry which provided

the inevitable and unrelenting

background to his life and songs.

Tommy

Armstrong's life (1848 to 1920) spans

the heyday of the coalfield that was

known as the Great Northern Coalfield.

In 1821 the Hetton company sank the

first shaft through the limestone on

the concealed coalfield in the East of

the county. With coal drawn from the

Hetton Lyons Blossom pit, the area was

set for a substantial expansion in

coal

production. The dependence upon the

London market for house coal eased as

other coal-using industries - iron and

steel and shipyards - expanded. In the

thirties and forties new pits were

sunk

in rapid succession in the East and

the

West of the county - Monkwearmouth,

Seaham, Murton, Thornley, Haswell,

Wingate, Esh Winning and Roddymoor.

All

these collieries were sunk at this

time. In the Stanley district Murns'

colliery was sunk in 1832 and the Air

pit in 1849. Tanfield colliery itself

was opened in this period.

So rapid and extensive was this

development that in 1850 a

correspondent for the Times newspaper

described County Durham as little more

than one huge colliery". In 1869, when

Armstrong would have been twenty-one,

there were 157 collieries and drifts

operating in the coalfield. Stanley

itself was ringed with collieries

owned

by the Lambtons and the Joiceys, John

Bowes and Partners and the new joint

stock companies like Holmside and

South

Moor and the South Medomsley Colliery

Company. Stanley was like the

Klondyke -

a place dominated by the mining of

black gold. In the last thirty years

of

the nineteenth century it expanded

enormously, transforming a rural area

into a major urban complex. For Tommy

Armstrong there were two Stanley’s,

first there was the business street,

with theatres, picture halls, shops,

churches and pubs". All this however

rested upon. the, industrial base of

the town, and the harsh conditions of

its workers - the miners - and their

families.

At the East end of the Louisa Terrace,

a railway line crossed the road to

serve the Oakey's Colliery screens and

siding, and these were behind a high

wooden fence about sixty yards long.

Three drab grey stone houses and

another fence of thirty yards, behind

which was an airshaft for the Louisa

Pit. On the opposite side of the road

beginning at the rail crossing was a

high brick wall with coal hoppers

inset, to provide for the delivery of

workmen’s free coal, and the lofty

brick buildings of South Moor Colliery

County Workshops. These buildings

enclosed the Louisa Old and new pit

shafts, railway sidings and screens.

The latter also catered for the Hedley

and William pits of Old South Moor,

their coals reaching the screens by

way

of the Hedley gangway with the use of

endless rope haulage.

In this time of great industrial

change

rural traditions were maintained. Men

kept pigs and a range of other

livestock. Women cooked all manner of

food, and also cleaned and sewed and

washed. 'Market Day’ remained an

important day in the weekly routine.

Something of this life is captured by

Tommy Armstrong in songs like ‘Stanla

Market’ (with the opening line if

you're bad and off your meat) and ‘Cat

Pie’ and ‘Hedgehog Pie’, while a side

of community relations which are far

from idyllic is developed memorably in

the Row in the Gutter. Daily life, and

its goings on, form the focus of these

songs. Others examine daily life in

the

pit, and here the gaiety and mischief

has a strong ascebic edge. ‘Oakey's

Keeker’ is a case in point.

The "keeker" in the Durham mines was

the man in charge of the surface of

the

colliery, Here was the place where the

coal, hewed with such effort and drawn

off the coal face in tubs, was

measured

and weighed. The miners were paid by

the weight of coal in their tubs and

if

there was too high a proportion of

stone payment was reduced. So

important

was the weighing on the surface that

miners had their own "check weighman"

to check the master's weights. In all

this, of course, the “keeker” was a

central figure.

A bad “keeker” could make a

considerable difference in the weekly

wage packet. And at Oakey's Colliery

in

the 1870's the miners had to endure

such a man. Joseph Elliot was

transferred to the pit from the nearby

Bank foot Colliery In Anfield Plain.

In

Durham people's biographies are

followed closely, and it was known

that

Elliot was born into a family in

Maiden

Law, To the people of Stanley he was

known as "Maiden Law Joe", and this is

how he is referred to by Armstrong, He

must, he says, have been born without

feeling or shame" that hairy faced

rascal Old Maiden Law Joe". It was

this

description which moved the “keeker”

to

take Tommy Armstrong to court for

libel. Tommy Gilfellon recounts how:

“Upon presentation of the offending

work to the clerk of the court and the

magistrates, he found smiles of

amusement on their faces too.

Enquiring

closer of Elliot as to what in

particular he objected to in the poem,

the magistrates were told that 'he

called me a hairy faced rascal'.

'Well' said the clerk of the

court, 'you still have your whiskers'.

The following day, the last two verses

of the poem appeared.” These verses,

incidentally, elaborated the insult,

suggesting that Oakey's “keeker” was

certainly bound for hell.

This story makes clear the way in

which

these son poems linked directly into

life and politics in the are

popularity

of the verses made them important

political weapons in a society

where "the masters" anticipated

respect

as part of their due. This aspect of

Tommy Armstrong's writings was

developed in other directions also.

His

songs were distributed and sold as

broadsheets, so too were his letters

and other pieces of prose.

At that time it was fortnightly pays,

Miners had to go to the Overman's

house

or office and he would tell you what

the pay was for you to draw on the

following night. There was a number of

ways in which, through fines and

deductions the infamous ("off-takes")

the miner's wage is cut back. For

example, seven shillings for powder

and

candles, twopence for the pick

sharper,

sixpence for house and coal, ninepence

for the doctor, sixpence for water,

ninepence for the weighman, half a

crown you got over much last time, two

shilling for the hospital, two

shilling

for picks and shafts and four

shillings

for striking at a putter. Obviously

the

poor coal miner could be quite

literally robbed by unscrupulous

management, there was no appeals

system

to challenge the’ off takes’. Fines

and "off-takes" were but one part of

the lines of potential conflict which

divided the masters and their miners

on

the coalfield. The Colliery Houses

were

owned by the coal owners and their up-

keep was a constant cause of concern.

The houses were slums and the miners

had no other choice but to live in

them, unfortunately the threat of

eviction was used by the coal owners

as

a great deterrent. In times of strike,

miners and their families were evicted

from these homes, This is the theme of

both Oakey's Strike and the South

Medomsley Strike. Oakey's Strike was

written by Armstrong at the Red Row

public house at Beamish Burn.

Tommy’s song ‘The South Medomsley

Strike’ (held in many folk circles as

the greatest mining song ever

written),

the aim was to put the record

straight,

to identify the masters who are to

blame, and to lambast the Candymen

who,

with the aid of the local down-and-

outs, eject the miners and the

families

from their homes. These are both

powerful songs in which colliery

managers and owners are described as

tyrants and their accomplices

threatened with boiling or hanging. It

is for those Candymen that Armstrong's

most severe wrath is reserved. These

men, local scrap metal dealers, earned

their name through their practice of

giving sweets to children in return

for

rags. In the North, their reputation

after strikes was lower than that of

the blacklegs.

The songs were written at a critical

time for the Durham miners. Throughout

the nineteenth century they had

struggled to form a trade union. In

the

1830's and the 1840's unionism was

defeated and union activists like

Hepburn and Jude blacklisted. In the

1850's and 1860's isolated miners like

Ramshaw and Rymer continued in their

attempts to build a trade union

amongst

miners in Durham. In 1869 the Durham

Miners Association was formed and this

was recognised by the masters in 1871.

With the recognition of the union went

the removal of the bond. But not the

removal of conflict and injustice. The

strikes in the 1870's were critical

ones which emphasised this fact. The

biggest strike, however, took place in

1892 when the whole of the Durham

coalfield was locked out. In this

strike (which took place in the middle

of a period when miners were

attempting

to form a base for national unity) the

Durham miners were alone. Although

they

received help from collections,

notably

from Northumberland, coal continued to

be produced in Yorkshire and Durham.

The Durham miners were defeated. At

that time Tommy Armstrong was 44 and

at

the height of his reputation as a song

writer.

|

|

This wonderful old photograph of

Tanfield with St Margaret's Church in

the background was loaned to us by

Society Committee member Michael

Tindall. His grandfather Jack Irwin is

the Blacksmith shoeing the horse.

|

|

His poem on the strike, ‘The Durham

Strike,’ was so to raise funds and

Armstrong appeared on platforms

throughout the county with Patterson,

the General Secretary of the Durham

Miners Association. This song is a

standard mining ballad which recounts

clearly where the blame lies, and the

debt the miners owe to their brothers

in Northumberland. It resonates with

another of Armstrong's standard

verses, ‘The Trimdon Grange

Explosion.’

This song, with its evocative opening

lines, "let us not think about

tomorrow lest we disappointed be", was

not written in dialect.

As the Durham Strike was a public

statement of right and wrong, so too

this lament to the dead of the major

colliery explosion at Trimdon Grange

(pictured above) ten years earlier. It

draws attention in a clear way to the

fates which affect coalminers, fates

which were made all too clear on the

coalfield in the nineteenth century.

But in 1851 there had been thirteen

major disasters on the coalfield in

which a total of 525 men had been

killed. In Armstrong's lifetime these

were followed by major disasters at

Seaham, Trimdon, Tudhoe, Usworth,

Ellmore, Fencehouses, Wingate and

Haswell. In 1909, of course, the worst

of them all took place in Stanley,

where 168 men were killed in the

explosion at Burn's Pit in the town.

In his lifetime Armstrong became

clearly identified as the “Pitman's

Poet". Any event of note (charabanc

accident or the opening of a railway)

would have to be recognised with a

verse from the poet. His son recalled

his father saying: "When you're

the 'Pitman's Poet' an looked up to

for

it, why if a disaster of a strike goes

by without a song from you they

say: 'What's with Tommy Armstrong? Has

someone drove a spigot in him an' let

out all the inspiration?'

As such it is likely that he wrote at

the time of the mine disaster in

Stanley. Perhaps this is one of the

many verses and songs that have been

lost forever. Perhaps too, by this

time, Tommy was past his prime. His

letters to the papers in his later

life

lack the sparkle of his earlier

writings. At the time of the First

World War he was deeply chauvinist,

and

writing verse attacking "Dirty Kaiser

Bill' (some signs of this chauvinism

can be seen in earlier verse like, for

example, The Row in the Gutter).

By 1870 Tommy was famous throughout

the

Stanley area not only as a poet but as

an entertainer too and had formed his

own concert party. Tommy himself was

no

singer, nor did he ever profess to be,

in fact his musical ability was, to

say

the least, limited. His greatest asset

as a performer was his razor sharp wit

which, with his gift for improvisation

of verse, ensured that he was never at

a loss for words. With his disguises

and his short, bandy legs he could

reduce an audience to helpless

laughter

by the simple process of standing

silently on stage for a minute or two.

He had a family of fourteen and a

considerable appetite for beer, as a

man, and a writer it is clear that the

muse lay in a pint of beer.

While some remember him fondly in old

age, others remember a rather

cantankerous man with bow legs and

sticks. Tommy had his poems printed

and

sold them at a penny a time in order

to

pay for his drink and in its turn the

beer often inspired new creations.

With the fame of his concert party

growing Tommy was a busy man but it

was

well known that he would always find

the time to bring his talents to the

aid of any charitable cause in the

locality. His troupe performed at and

organised innumerable functions to

raise money for victims of misfortune

and pit disaster, for reading rooms

and

the funds of the struggling miners'

union. His work was committed to

improving the lot of the miner and

displayed a profound class

consciousness, a noticeable faculty

for

criticism of society. The 1880s

and '90s was a militant period when

the

membership of the miners' federation

rose dramatically to 200,000. Strikes

and lockouts were frequent and the

pitmen were at last combining to

present a solid front to the coal

owners. Their movement was by no means

revolutionary, nor did it have any

long

term ideological goals and the

pitmen's

attitude is mirrored in their songs of

the period, wherein they call for the

redress of immediate grievances. These

songs also served a practical purpose

in as much as they also raised money

for the hungry families of strikers

when they were sung in the streets.

In the years to come, to remember

Tommy

was not to romanticise. Rather it is

to

see his songs as an enormous personal

achievement whose main strengths lies

in the firm roots they took in the

experiences of the Durham mining

communities. Perhaps it is fitting

that

he is best 'remembered for the songs

he

wrote about these people. ‘Funny Names

in Tanfield Pit’ is an ingenious play

on the odd family names represented in

the colliery. In this it resonates

with

the enormous preoccupation with the

detail of local issues which dominated

Durham mining culture and its sense of

humour. This is clear too in his most

famous song ‘Wor Nanny's a Maisor’

which, in its tale of mishap,

drunkeness and carefree abandon stands

out as a very special Northern song.

|

|

Extract from ‘Around Burnopfield’ by

John Uren:

On Saturday 26 August 1911, a loaded

charabanc, known as a Coronation Car,

carrying members of the Consett Co-

operative Choir from Consett to an

annual contest at Prudhoe, crashed

into

a tree on Medomsley Bank when its

brakes failed. Nine of the choir were

killed instantly and a tenth died

shortly afterwards; many others were

injured. Members of the Burnopfield

Ambulance Brigade, who had been

attending their annual flower show and

sports day in Thompson's field at

Bryan's Leap, got into the shafts of

their horse-drawn ambulance and

manhandled it to Medomsley Bank while

someone fetched a horse.

The Pitman’s Poet Tommy Armstrong paid

tribute to the dead and injured in the

following poem. He didn’t write his

commemorative poems to make money, he

genuinely felt that he had an

obligation to pay tribute in verse.

The Consett Choir Calamity

Scripture tells us very plain

to "Think

not of to-morrow,"

Because our happiness and joys may

quickly turn to sorrow.

How many cases have we known up to the

present time

Where death has called away young men

and women in their prime.

Some we knew that suffered long in

bed,

both night and day

And others, in the best of health,

were

suddenly called away,

When the appointed time has come, to

death we cannot say.

"I'm not prepared to go just yet, call

back some future day.

Death will take no bribery, or one

thing would be sure;

The Rich would live, and Death would

only call upon the poor,

We know there's danger everywhere, no

matter where we go,

Look at the sad calamity - going to

Prudhoe Show.

A happy band of Vocalists from Consett

went away,

To join a Singing Competition which

was

held that day.

The vehicle which they'd engaged at

Consett did arrive,

The weather was both fine and fair,

and

pleasant for a drive.

The vehicle with its passengers which

numbered twenty-eight,

Delayed no time at Consett, lest they

should be too late;

A pleasant smile was on each face all

hearty and so gay.

They all joined in with one accord, to

sing while on their way;

They sang with voices loud and sweet,

in praise of God on high.

but little thought that afternoon that

some of them would die.

Death was riding with them, but little

did they know,

That not a one amongst the lot would

see the Prudhoe Show.

When they arrived at Medomsley, five

passengers were there,

Waiting for to join their friends,

their pleasures for to share,

The vehicle stopped and took them in,

they each one took their seat,

They moved away, but never thought of

danger, or the troubles

they would meet.

All went well until they reached a

bank

both steep and long,

On going down it could be seen that

there was something wrong

The vehicle ran much faster than what

it ought to go,

The danger that their lives were in

not

one of them did know

The driver did his very best, the

vehicle for to guide,

Thinking of the passengers that he had

got inside;

The brake refused to do its work, none

of the company knew,

The driver sat and did his best to

bring them safely through;

There was no chance of jumping

out, 'twas useless for to try,

They had no other chance but sit,

which

made their end so nigh;

And when he had lost all control -

exhausted as could be

The vehicle and its passengers ran

smash into a tree.

As soon as the disaster, the news was

quickly spread

That twenty-five were injured, and

nine

were lying dead;

The ambulance, and doctors too, were

soon upon the ground

With stimulants and bandages to dress

up each one's wound.

One young man named Pearson, was

injured so that day,

On going to the Infirmary, he died

upon

the way.

We hope those Ten have landed safe

into

the Home above,

Where all is Happiness, and Peace, and

Everlasting Love.

|

|

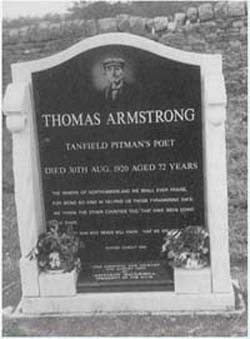

Never a rich man, Tommy suffered more

and more from want in his declining

years. Concert parties and

entertainments were arranged to assist

him, little enough for a man who had

kept Stanley laughing for fifty years.

He died at Tantobie on 30th August

1920

at the age of seventy-two. A few lines

from his poem 'The Durham Strike' are

engraved on his tombstone:

The miners of Northumberland we shall

for ever praise,

For being so kind in helping us those

tyrannising days;

We thank the other counties too, that

have been doing the same

For every man who reads will know

that

we are not to blame.

The tombstone was unveiled on 9th

August 1986 by Arthur Scargill,

President of the

National Union of Mineworkers.

The Works of Tommy Armstrong:

The Trimdon Grange Explosion

The Consett Choir Calamity

The Blanchland Murder

The Durham Strike

Oakey’s Keeker

The Ghost Thit’ Anted Bunty

The Cat Pie

The Hedgehog Pie

Sheel Raw Flud

Dorham Jail

Th’ Row I’ Th’ Guuttor

Marla Hill Ducks

Oakey’s Strike

Corry’s Rat

Tanfeeld Lee Silvor Modil Band

Th’ Skeul Bord Man

Sooth Medomsley Strike

Bobby En Bet

Funny Nuaims It Tanfeeld Pit

Th’ Wheelbarrow Man

Th’ Row Between Th’ Cages

Nanny’s A Maisor

Stanla Market

Th’ Borth E Th’ Lad

Th’ Nue Ralewae

Tanfield Brake

The Kaiser And The War

Murder of Mary Donnelly

Old Folks Tea

Reference: ‘Polisses & Candymen’

Edited by Ross Forbes

Published by The Tommy Armstrong

Memorial Trust.

WHY NOT LOG ON TO THE FARNE FOLK

ARCHIVE RESOURCE (LINK BELOW), home

of

Northumbrian music online. From here

you can access 4,000 songs, tunes,

sound recordings and photographs from

across North East England, bringing

the

musical heritage of the region alive.

Folk Archive Resource North East is an

online archive of songs, tunes and

sound recordings from Northumbria

created by Gateshead Council, the Sage

Gateshead and the University of

Newcastle upon Tyne. The archive

features a number of original song

books and manuscripts by Tommy

Armstrong.

Farne Folk Music |

|

THE MINER’S FAREWELL

A PITMAN ON HIS CRACKET SAT

WITH PICK IN HAND THE COAL TO CRACK

BUT NOW ALAS HIS SWEAT AND TOIL

ARE FORCED ASIDE BY GAS AND OIL

NO MORE IN TUNNELS LOW AND DARK

WHERE ONCE HE STROVE TO MAKE HIS MARK

HE WALKS ERECT IN GOD’S SUNLIGHT

SO PITY NOT THE PITMAN’S PLIGHT

HE’S CHANGED HIS DARKNESS FOR THE

LIGHT

ANON

The following poem was received by

E.Mail. We are pleased to publish it:

THE LAST NORTHUMBRIAN COAL MINE

Six hundred years of sweat and toil

In that deep and dark abyss

The entrepreneur has spoken

Blown a tasteless goodbye kiss

Two hundred men and boys

Crushed and gassed and drowned

New Hartley, 1862

Beneath that cold, cold ground

At Burradon, 1860

Seventy six were burnt and maimed

They were only slaves and chattels

No need to be ashamed

No sick pay, no such benefit

No mercy from the rich

Like the Irish in the famine

Left to die within that ditch

Families torn asunder

Communities destroyed

Where the hell was the compassion?

The obligations null and void

We will not forget you Thatcher

And your heartless decimation

Your ultimate achievement

A bitter, divided nation

Northern coal helped build this

country

While the Irish laid the rails

Betrayal comes easier than honour

All that are left are old men’s tales.

Written By John Robinson

Northumberland, UK following the

closure of Ellington Colliery (The Big

E)

|

|

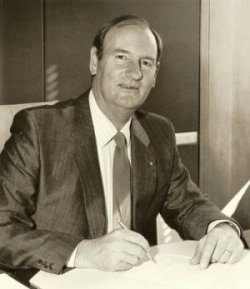

A new local book has been published

about Tommy Armstrong – ‘The Pitman

Poet’. The book was launched at the Lamplight Centre, Stanley on Thursday 18th November at 11 o’clock.

The launch was a huge success with a room packed full of people clamouring for a copy, each one signed by the author.

Tommy’s famous songs include such

classics as ‘Dorham Jail’, ‘Nanny’s A

Maisor’ and ‘Trimdon Grange Explosion’.

What makes this book unique is that it

has been written by Tommy’s grandson –

Ray Tilly pictured below.

|

|

“Ray was born at Eighton Banks in 1934, he attended Chester-le-Street Grammar School then became a Police Cadet with Durham Constabulary for 18 months. In 1952 he joined the Army and was stationed at Windsor for three years then on leaving the Army, he stayed in the south and joined the Police Service. Ray spent many of his 30 years service in the Criminal Investigation Department and he rose to the rank of Chief Superintendent before retiring from Thames Valley Police in 1985.

He settled in Buckinghamshire, where he still lives, then worked as a Security Consultant until he retired in 2002. Since then, he has been engaged with researching the family history of his wife’s and his own ancestors.”

Ray’s book is an attempt to ‘set the

record straight’ about the life of his

grandfather.

Many things have been written and said

about Tommy, and Ray separates fact

from fiction.

Included in the book are thirty

previously published works by Tommy

and a further sixteen unpublished

works.

Also included are the poems and story

of Tommy’s son – William Hunter

Armstrong – Ray’s father.

The book is published by Newcastle

company Summerhill Books and is priced

£9.99. The book has over 100

illustrations.

For further information contact Andrew

Clark on 07971 859 401

|

|

NEW FOUND WORKS OF TOMMY AMSTRONG

The launch of the book ‘Tommy Armstrong: The Pitman Poet’ by his grandson Ray Tilly, was held at the Lamplight Arts Centre, Stanley on the 18th November 2010 where Ray met Moira Corker who is linked to the Armstrong family. Moira had a number of works by both Tommy and his son William Hunter Armstrong which she kindly gave to Ray. Amongst them are a number which have never been published so Ray has compiled them into a book, with an explanation of how they have been found after all these years. Of particular interest is the fact that it was always thought Tommy must have written about the tragic ‘West Stanley Explosion’ in 1909, when 168 men and boys were killed at Burns Pit but no copy of a poem could ever be found in recent years. Tommy’s poem about that disaster is included in the book.

The book is only available by sending postage stamps to the value of £1.20 and a cheque for £2.50 to ‘The Tommy Armstrong Society’, c/o 10 Rupert Avenue, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, HP12 3NL.

|

|

|

|

A memorial plaque has been attached to the gate of the Tanfield Cemetery, a fitting tribute to Tommy.

|

|

|

|

|

|